This post is also available in:

ABOUT THE EXHIBITION

TEOR/eTica proudly presents two solo exhibitions by artists based in Central America who in recent years have taken a particular stand on the possibilities and ideological implications of design.

DOWNLOADABLE POSTER OF THE EXHIBITION

March 5th – July 2014

HOPEFULLY THE SUN WILL HIDE ME

Alberto Rodríguez Collía and Andrea Mármol

The project by artists Andrea Mármol (Guatemala, 1988) and Alberto Rodríguez Collía (Guatemala, 1985) revolves around a particular way of operating in set design. For the past two years both artists have been working alongside the prominent film director Julio Hernández (Guatemala/USA, 1975) designing the set for his movie “Ojalá el sol me esconda” (Hopefully the sun will hide me). The film tells the story of Héctor, a young man of quiché indigenous descent, from Totonicapán province, who plays in a punk band. One day, on his way to the village to visit his sister, Andrea, Héctor finds out that a drug-plane has crashed near his house. The siblings decide to go investigate and they find several kilograms of cocaine amongst the rubble. This fictitious story of two young indigenous-punks in the desert is the starting point for the movie, whose central theme develops around a real event “la masacre de la finca Los cocos” (The coconut farm massacre), one of the most morbid events in Guatemala’s recent history.

In December 2011, in the department of Petén, the border region with Mexico, 27 farm workers were assassinated and beheaded. Those responsible for the crime were part of the Mexican cartel los Zetas, which every year acquires more power in Central America, increasing the already high homicide rate of the region. One of the most visceral images of this massacre, documented by the police and uploaded to the internet, was the dismembered bodies of the victims and the heads scattered all over the farm, paradoxically called “The coconuts”. In order to be able to narrate this tragic story, the film’s director asked Mármol and Rodríguez Collía to devise a way of designing the set in which the dismembered bodies and other elements of the script could be represented.

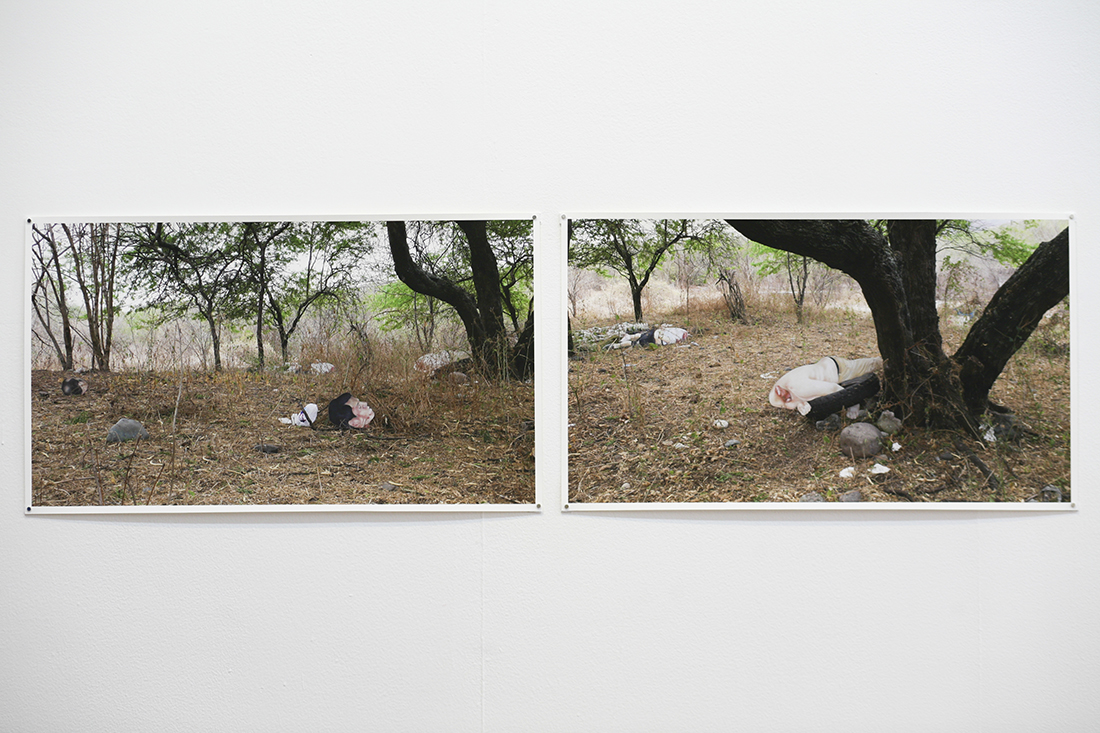

Based on the survivors’ testimonies and the police report of the massacre, the artists opted for a simple, yet absurd and unconsciously perverse resource. They designed a set in which images of decapitated bodies were painted on human scale size wood figures. The chosen realist technique made the camera’s lens capture an uncanny relation between the live actors and the wooden pieces of bodies. At the same time, the surreal strategy of this low-tech method challenged the effects of digital post-production, and made great use of the economic limitations in filmmaking.

FAMILY PORTRAIT IN HELVETICA

Mimian Hsu

Mimian Hsu (1978, Costa Rica) has been invited to intervene TEOR/éTica’s façade as part of her project Family Portrait in Helvetica, 2014. The display of certain of her previous pieces and a new series of photographs related to Chinese immigration in Costa Rica will accompany the exhibition. For the façade, Hsu (of Taiwanese descent) has created a design chart where she displays the ways in which fragments of letters and numbers, typed in Helvetica font, can been used to write the artists’ name in Chinese characters. What may appear to be the coming together of two different systems of representation, results in a peculiar form of cultural hybridity.

Fonts, typography, the aesthetic appearance of letters, are the most immediate forms of design that we face daily, from the use of keyboards and screens, to publicity’s constant bombardment of written messages. The style of a font embodies affection, emotions and ideology. Designers, publicists and artists comprehend the power a letter’s style has over a person’s subjectivity. This awareness of the font’s effect can be traced within art history itself, in text based conceptualist practices. For example, Joseph Kosuth’s mythical pieces on the tautologies about the representation of objects, would not have been assimilated in the same manner if the font of the words that appear in his works had been done using a more baroque, gestural style of writing. The visual “neutrality” in the type of font used in conceptualist strategies like Kosuth’s derives from the cultural identification that the West has given to certain typography which is assimilated as being aseptic, sterile, hygienic and therefore, universal.

The “hygiene” of a font like Helvetica motivated Hsu to question its homogenizing power within design. In the large-scale Chinese character that appears on the left of the façade, the western modern letters and numbers in Helvetica have been modified, almost forced, to adapt to an East Asian, gestural type of writing. With her work, Hsu appears to have created a fictitious typography, pointing out the limits of cultural translation within a so-called universal design, one which Helvetica claims to represent. It is important to note that Helvetica font in itself has assumed a unifying role within global economy, making it the preferred style of several corporate brands. Some of which are listed in the intervened façade.

Meanwhile, the works in the exhibition room belong to the artist’s body of work that explores historical interstices related to the flow of Chinese immigration to Costa Rica, one of the most significant in Latin America. For example, her work Colonia China (2014), documents the ghettoized Chinese cemetery in the Caribbean side of the country. While No.1674, Sección Administrativa, Versión 2 (2012) is an installation based on a letter written in 1907 by Chinese railway workers who were asking the Costa Rican government for a permit to bring their wives and children to the country. The work is comprised by the letter’s text embroidered on to a chinoiserie bed sheet silk, often given as a gift to newlyweds.

Inti Guerrero

Curator

With the support of HIVOS-Arts Collaboratory

INFORMATION

ARTISTS: Alberto Collía, Andréa Mármol, Mimian Hsu

VENUES: TEOR/ética

This post is also available in: