This post is also available in:

ABOUT THE EXHIBITION

What happened to Cocorí?

09 oct 2014 – 22 Feb 2015

Curated by: Lina Castañeda

Marton Robinson is a Costa Rican artist living in San José. Like any other citizen, he takes the city bus everyday. Even though the bus is packed with people, two or three times a week, the seat next to him remains empty. Oh! I forgot to mention that Marton is black. And no, I don’t believe there is any other reason, besides him being black, for people to avoid seating next to him.

Centuries of slavery, segregation, prejudice, slander, discrimination and disregard have formed a sad and long chain, forged in the belief in black racial inferiority. This belief is still present and has led to situations of rejection, like the one Marton experiences on the bus or what black players endure in stadiums during a soccer match, when fans imitate gorilla sounds to insult them.

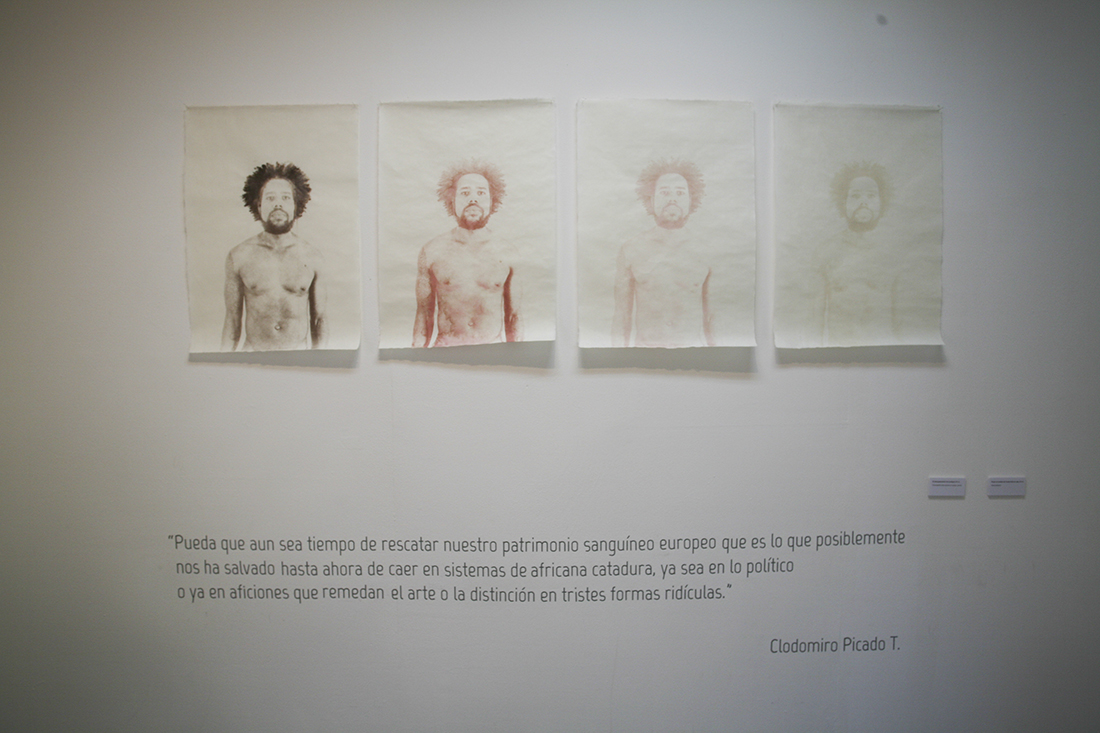

Different ideologies and scientific theories have argued that the black race is inferior, acting as bio-political attempts to control and punish bodies, classifying and hierarchizing them axiomatically under the protection of the so-called “scientific objectivity”. One of these theories claimed that in order for black people to “improve the race” and become white, it was necessary for them to reproduce with white people for four generations. El blanqueamiento de la sangre(The whitening of the blood) (2014) is a work composed of four silk-screen prints. The “ink” is a mixture of blood and semen from the artist himself. His portrait is repeated in each print, each one coming closer to the “coveted” white.

Black people are not part of the traditional imaginary of national identity in Costa Rica, which defines the Costa Rican as descendant of Europeans who mixed little with other races. The afro-costarican does not appear in national representations. A good example of this is the mural Alegoría al café y al banano (Allegory to coffee and bananas) (1897) by Italian Aleardo Villa, which can be seen in the lobby of the National Theatre of Costa Rica and is also the illustration of the old five colones bill. Referred to as “the most beautiful bill of the world”, even though part of the scene appears to takes place in Puerto Limón, none of the peasants and workers represented in it are black. In Untitledfrom the series Money Talk (2014) Marton replaces some of these characters with these forgotten blacks by overlapping images in a seemingly false way.

Likewise, in another attempt to forcibly incorporate blackness into the tico imaginary, the artist dresses up in traditional Costa Rican costumes two Jolly Niggers, iron piggy banks popular in America in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. These slots, the Negriti-ticos (2014), are accompanied by a narration of a story of Marton’s family, recalling how black Jamaicans, as part of a welcome show, would catch with their mouths coins thrown by visitors coming in from the European cruises.

However, it would be inaccurate to claim that blacks are completely excluded from the current Costa Rican identity. The main area where they can and should Put Costa Rica’s name up high (like the title of the work Poner en el nombre de Costa Rica en alto, 2014) is sports. Sports represent national pride against foreign adversaries. A black man may be a “fucking nigger” in the stadiums of the Central Valley, but not when he is scoring goals at the world cup. In that moment he is tico pride, worthy of national representation, he is El negrito más feliz de Costa Rica (Costa Rica’s happiest black boy) (2014).

If you are wondering what happened to Cocorí, the mythical and literary black boy from Puerto Limón, or believe that racism is an issue that has been overcome, you are welcomed to visit this room.

Lina Castañeda.

Curator

Marton Robinson studied Physical Education. He is currently completing an MA in Integral Health and Human Movement and a BA in Art and Visual Communication with an emphasis in Printmaking at the National University of Costa Rica. He works as a teacher and in the development of projects related to art and visual communication, health and human movement.

INFORMATION

ARTISTS: Marton Robinson

VENUES: Poligráfica

This post is also available in: