This text is included along several images of her work in the book Virginia Pérez-Ratton. Transit through a doubtful strait (2012) published by TEOR/éTica. It is based in the documents VPR herself prepared, updated and organized for her exhibition Re-puesta en escena that took place in May 2010 in Des Pacio (San José).

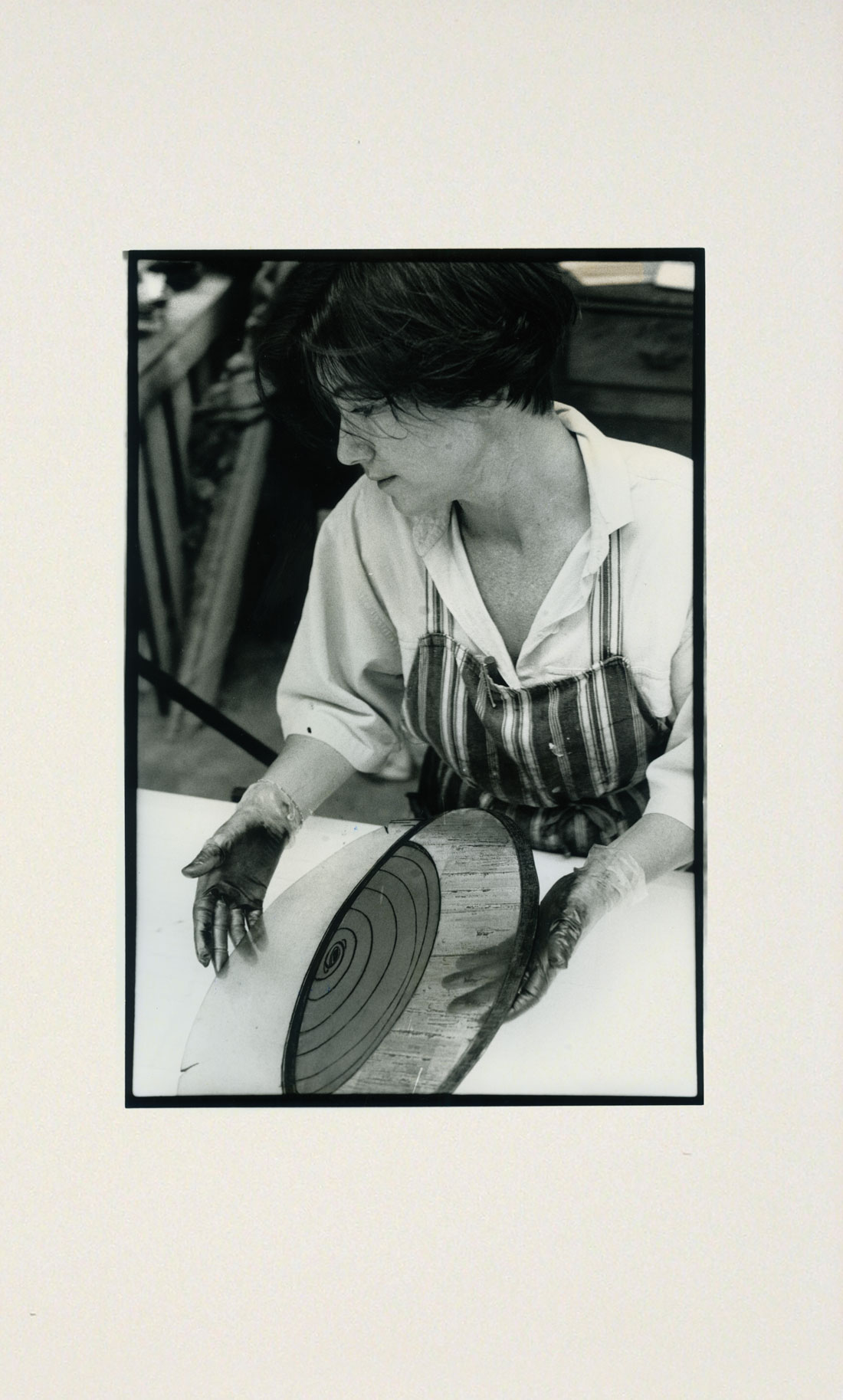

Virginia Pérez-Ratton began her art practice after working as a French literature professor at the University of Costa Rica (1971-1980). Beginning in 1981, she participated in various workshops with local artists – drawing with Grace Blanco, painting with Lola Fernández and engraving with Juan Luis Rodríguez. She took part in the CreaGraf program at the School of Fine Arts (University of Costa Rica), alongside Hector Burke, Emilia Villegas, Rudy Espinoza and Joaquín Rodríguez del Paso, among others. In 1988, she informally attended engraving workshops in the School of Decorative Arts in Paris, and then, in 1989, she enrolled in the Municipal School of Decorative Arts in Strasbourg, France, where she specialized in lithography and experimental graphic techniques.

After her return to Costa Rica in 1990, from her “Atelier La Tebaida”, she devoted herself to developing a personal language in the graphic arts. Her most significant work in this field is, certainly, the series of engravings “Juego para trece más una memoria”(1992). About this series, comprised of 14 engravings, Virginia writes: “My graphic work seeks freedom from within a technique that usually, once the matrix is finished, imposes strict rules of repetition. At a time when we are deluged by the industrial reproduction of immaculate and infinite images of all sizes, I explore editing in ways that allow me to produce unique multiples: I present fourteen editions of equal number and format, in which each copy contains slight voluntary variations that, far from affecting the unity of this edition, make it cohesive through the reiteration of the fortuitous.”[2]

Starting in 1991, she began to show an interest in the practice of working with found objects, exploring assemblages that would incorporate both the graphic arts and these found or recovered elements. She also uses painting to draw a bridge between the object and its representation or abstraction.

In 1992, an earthquake shattered much of the glasses and cups in her home. That broken glass became a central element in the sculptures and installations she developed at that time. In 1993, she presented this body of work, which fluctuated between painting and assemblage, in a solo exhibition, “rupturas y transferencias” at the J.García Monge gallery (San José). Rolando Castellón recalls that this work represented a turning point in the career of the artist, when he says: “She went from using the machine -the etching press- to produce her work, to constructing her sculptures by using elements of “reality”, in this case the evidence of a fortuitous geologic event, such as the earthquake. She took all these pieces of glass in a very sensitive manner and placed them so that they carried a sense of the ephemeral, of the living. What she was presenting at that time was, in some way, an illustration of the earthquake, ‘living art,’ sculptures with elements taken from reality and specific events, with an emotional component that interested me and led me to write a small text, not a formal text, but something we in Nicaragua call a ‘prosema’.” [3]

From then on, she focused her research around the reutilization and transformation of everyday objects that bear some emotional memory, as in the collections of china or broken glass (Fregadero Blues, 1997) or the installation that includes a sequence of dresses from childhood to adulthood (Hoja de Vida, 1995). The idea and images of vulnerability, rupture, fragility, as well as the influence of the immediate context, and the stereotypes that social structures confer to human relationships, are crosscutting in her work.

Broken glass and fragments of pottery would become be a key element in several works by Pérez-Ratton. She utilized them in Pecera (2000-2010), a glass urn the artist filled over the years with crystal from everyday broken glasses and cups; in Souvenirs exclusivos(1999), an installation of several small glass ‘suitcases’ in which the artist kept glass fragments accumulated during her or her friends’ travels and in Tricolor (1992), among others.

In 1994, a jury composed by Gerardo Mosquera (Cuban critic and curator), Aracy Amaral (Brazilian critic) and Jaime Suárez gave VPR the First Prize of the 1st Sculpture Biennial of the Cervecería Costa Rica for the work De vidrio la cabecera (1994). A recovered metal cot was presented with a clear glass mattress and a textured glass pillow with flowers, surrounded with white cotton lace. The title refers to the sexist implications of the popular “ranchera” song La cama de piedra.

That same year, she accepted the direction of the newly created Museum of Contemporary Art and Design (MADC) and focused her practice on research, management and curatorship, setting aside her own artistic production.

During that time, two procedural pieces stand out: Fragmentos de muda (1999-2005) andJuego de muda incompleto (1999-2003). In their many versions, these two pieces take up the idea of the fragments, this time using elements cast in bronze and finished in an oxidized silver-plate, based on casts made from the artist’s own body, “as if I had shed my skin or, furthermore, as a metaphor of flaying.”[4]

Tamara Díaz Bringas wrote, in 2003: “From engraving to installation and assemblage, VPR’s proposal has resorted to personal or household objects, full of history and affection. From dresses to broken pieces of household china, these objects carry memories and experiences of fragmentation.” [5]

Notes

[1] This text is part of the publication Virginia Pérez-Ratton. Transit through a doubtful strait. It isbased in the documents VPR herself prepared, updated and organized for her exhibition in Des Pacio (San José), in May of 2010.

[2] Virginia Pérez-Ratton, in a compilation of personal texts about her work. This excerpt is from 1992.

[3] Approximative transcription of a conversation with Rolando Castellón 2012. The ‘prosema’ that he mentions is reproduced in page 384.

[4] Virginia Pérez-Ratton, text about Juego de muda written in 1992 and modified by herself in 2010.

[5] Diaz Bringas, Tamara. En el el trazo de las constelaciones. San José: Ediciones Perro Azul, 2003.