This post is also available in:

ABOUT THE EXHIBITION

The place where i am is disappearing

Feb 28 – May 26, 2013

Curated by: Inti Guerrero

The work of Mariana Castillo Deball deals with ways history has been written, archived, organized and disseminated. A significant number of works are specifically based around the formats in which archaeological objects have been exhibited throughout the years via copies, prints, books and even réplicas. For the execution of each of her pieces, Castillo Deball embarks on a painstaking process of dissecting archives and becoming familiar with the bibliography surrounding the historical object that motivates her practice. Nonetheless, her works propose a visual language of a certain materiality which both transcends the mere archival appropriation and at the same time claims distance from a fetishization of the past.

For this exhibition, the artist has realized an animation and a site-specific drawing installation, based on the Borgia Codex, one of the most complex pre-Columbian manuscripts from the central plain land of what is now called Mexico. The Borgia Codex is considered to be of great value in understanding the ways in which Amerindian civilizations intertwined mythology, religion and calendrical systems used for agriculture. The manuscript came to light in modern times at the end of the 19th century, when voyager and scientist Alexander Von Humboldt wrote about its existence among the belongings of Cardinal Stefano Borgia. Cardinal Borgia, who lived in Rome, had acquired the manuscript in the antique collections of the Giustiniani family. After the Cardinal’s death, the Codex named after him became property of the Vatican, where it still lays on a shelf of the Apostolic Library.

The codexes are folded panel books written on various parts of deer skin and paper, which are sewn together in such a way to create a long strip which is then folded like an accordion. The Borgia Codex consists of 37 panels, painted on both sides. Its creators painted scenes and glyphs used for calendars by the Mixtecas. The specific location where it was found in Mexico is still uncertain. However, throughout the 20th century various iterations of anthropological theses have determined that its figures have certain characteristics which can also be found in other pre-Columbian codexes that were excavated in the Mixteca highlands, the mountainous areas south of the city of Puebla.

The first time that the content of the Codex Borgia was made public, was when the Irish antiquarian Lord Edward Kingsborough made a series of hand-made paintings of a number of panels of the codex, which were part of a publication he titled “Antiquities of México” (1831-1848). In the last decade of the 19th century, that edition of “original” replicas, was later transferred to lithographic facsimiles as part of a new edition of prints of various pictorial codexes coming from the central valley of Mexico. In this industrial and mechanical reproduction which had much greater distribution, the panels of the Borgia Codex were accompanied by descriptive and interpretive comments by the then famous German anthropologist Eduard Seler. The gaze of Seler, found in his essay “Der Codex Borgia und die verwandten aztekischen” (The Borgia Codex and Aztec Pictograms), was already informed by a previous description to the codex made by Mexican Jesuit José Lino Fábrega, who was fluent in Nauhtl and was familiar with the meaning of the figures in the codex. To be more precise, it was actually Fábrega’s memoirs quoted by Humboldt in his memoirs of the codex, the one that Seler referenced in his thesis. In this way, the widely distributed printed and published voice of Seler, illustrated by a Westerner’s (Kingsborough’s) reproduction of the original codex, further instigated a successive chain of appropriation, interpretation and reproduction of knowledge, always guided through the eyes of others.

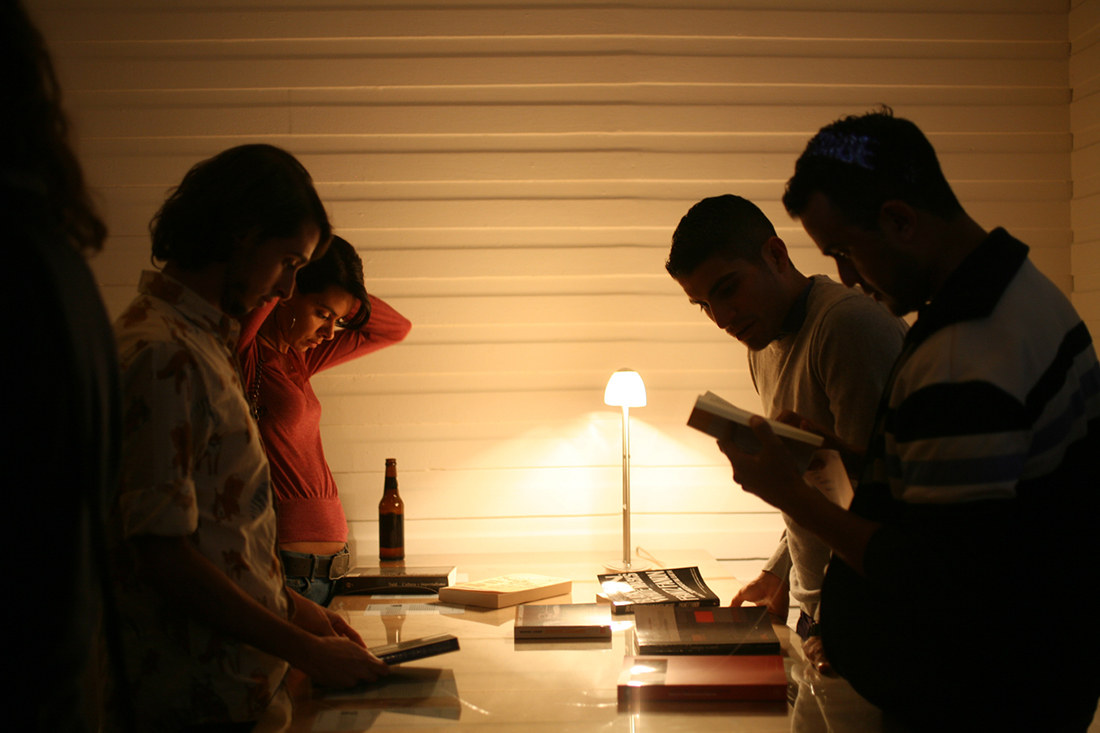

Throughout six months, Mariana Castillo Deball became familiar with the technique of the codex’s pictograms, in order to produce her own simplified compositions. After some time, she started to trace and compare all chains of interpretation and the diverse representations of the codex, looking closely at the cannibalism of references and sources found in the writings of those who previously studied this manuscript. The drawings on the walls of TEOR/éTica juxtapose the diverse interpretations that best illustrate the historiography of the codex. Different to the gaze of cleres, scientists and colonial voyagers, whom were seeking to decypher the cultural significance of the rituals been represented in this manuscript, whose meaning was sometimes moralized, the gaze of Castillo Deball towards the codex appropriates the intrinsic fiction within this cultural translation by bringing us closer to both the cosmology of the artifact and the historical corpus of its former owners.

The languages of the people who in some way or another became owners of the meaning of the Borgia Codex, constitute the framework of “El donde estoy va desaparenciedo” the solo exhibition of Mariana Castillo Deball in TEOR/eTica. The audio which one hears in the gallery space is composed by voices which start from Nahuatl, Spanish, Italian, and German, ending in English, showing the different subjectivities that have rationalized the information of the codex throughout history. The voice of its first interpreters constructed categories for what till then was unknown among the metropolitan world of European imperial centres. This construction of knowledge of a pre-Columbian past established itself through the scientific practices of collecting, classifying and taxonomy. For example, by transferring the codex’s panels to lithographic prints, later to be published along with his narration, anthropologist Eduard Seler dissected the original narrative of the codex, by simultaneously establishing his possession of the knowledge of the artifact. The exercise of power of this scientific practice was established due to the intrinsic power of displaying what was been described. But in the case of the codex, its exhibition is never physically real, as it would be the case of an artifact of this kind within an ethnographic museum. In the case of the codex its display occurs through reproduction and publishing. This condition of circulation through printed matter may well have disseminated even more knowledge about the codex than the logics of exhibition display within a petrified museum. It was then precisely due to its mechanical reproduction, that 19th century anthropological knowledge on mesoamerican civilizations began to circulate within an academic and cultural field which was simultaneously emerging.

Just like an ethnographic museum, the interpreted codex, in its modern, printed version, constructed an alterity to the reason which was interpreting it. There is no doubt the codex was for the Mixteca people a utilitarian tool (a calendar) for what science taught us to call agriculture. However, its interpreters, who comprehended reason as a secular manifestation, decided to petrify the use of the codex due to its cosmological and religious structures. In other words, the anthropological study of other cultures and other forms of knowledge, were part of an “inclusion” of alterity to Western science’s universalist humanism which tended to define the rest of the world through a single reason.

INFORMATION

ARTISTS: Mariana Castillo Debal

VENUES: TEOR/ética

This post is also available in: